Visiting Venice is always such a rewarding, unique experience. Charming narrow streets, countless little bridges over the canals, beautiful old buildings – all accompanied by loud Italians and the lingering smell of fish. No cars in sight, only boats and gondolas, sailing smoothly over the emerald waters. And every other year, as a cherry on top of it all, world’s best visual art comes to town thanks to the Venice Biennale.

And what an opportunity this was, first and foremost, to stand in front of the work of leading female Surrealist artists. I start there, because that was curator Cecilia Alemani‘s starting point as well: the title of the Venice Biennale 2022, “The Milk of Dreams“, comes from a book by artist Leonora Carrington, in which she “describes a magical world where life is constantly re-envisioned through the prism of the imagination.” Latching onto this idea of ongoing transformation, the Biennale focuses on the human body, its relationship with itself, with technology, and with nature. The central exhibition and its 213 predominantly female artists, together with the 80 national pavilions, took me on a journey that I can honestly describe as a positive one overall.

To define art has always been a challenge, and there is no one definition of it either. Personally, I wholeheartedly agree with those who say art should make you feel something, teach you something about the world, and yourself. I felt and learned so many things while walking the grounds of the Giardini and the Arsenale. Most of the time over the course of my two-day visit, I let the art take me in and absorb me without prejudice. Some of it did a really good job of imprinting itself into my memory forever, be it from artists whose work I’ve admired for years, or those unfamiliar to me who have now left a lasting impression, to say the least.

Without further ado then, let’s go through some highlights of the Venice Biennale 2022.

The Milk of Dreams, Central Exhibition

The central exhibition of the Venice Biennale 2022, to me, was an escape from a utopian reality into a world that unapologetically, almost exclusively celebrates female art. While kudos are to be given to Mrs Alemani for her conceptual thinking, it is the artists she brought together who paint such a complete, extraordinary picture of the human existence, of the female experience, to the point where I forget everything about other art outside of this exhibition. It’s almost like I don’t need it, like everything I ever needed to understand or relate to is right here – in a 1940 Ithell Colquhoun painting, or a Mire Lee installation from 2021.

I start with the Giardini and the central venue there, very easy to get lost in or perhaps even completely miss parts of the exhibition if one’s not careful.

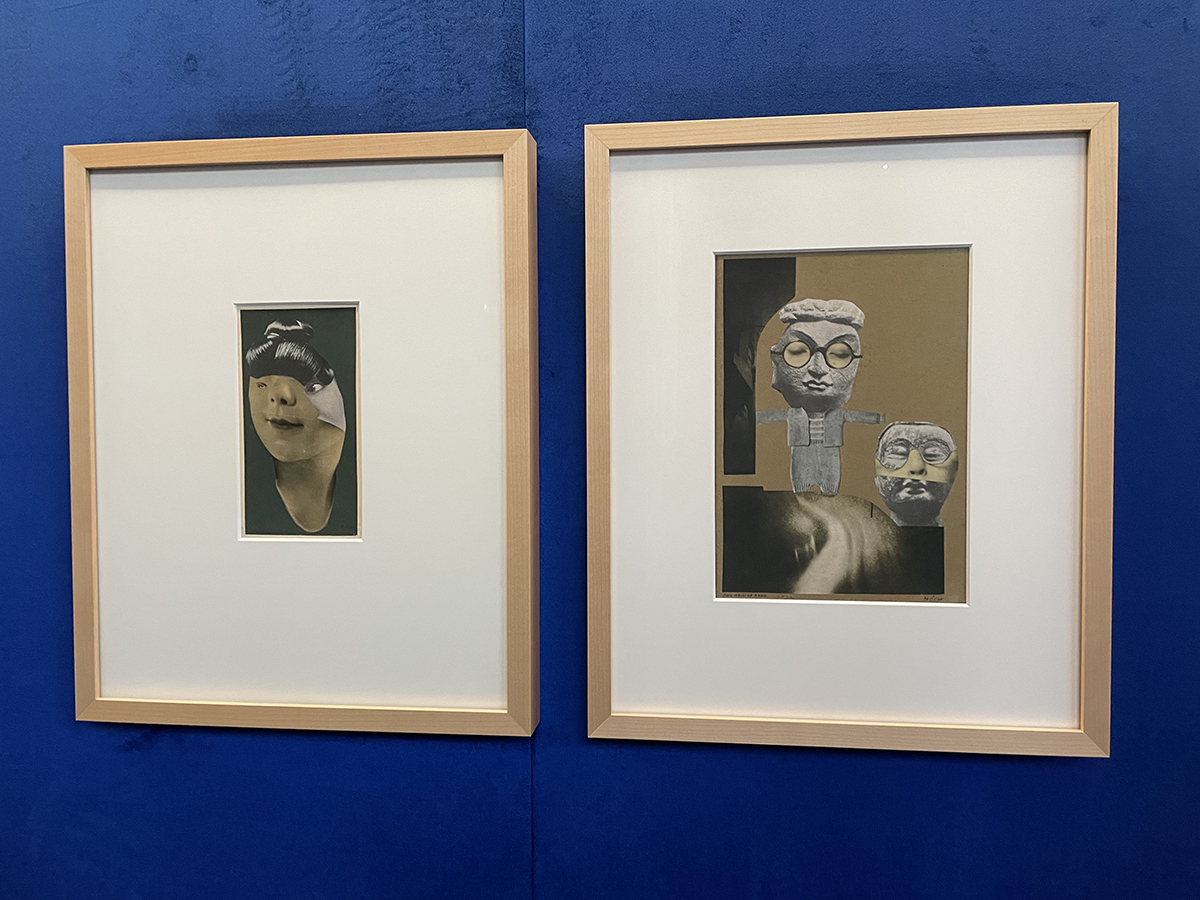

“The Witch’s Cradle” is one of the five capsules conceived by Mrs Alemani, as a sort of a “show within a show.” A room clad in soft, mustard-colored carpet, it focuses on an all-encompassing “metamorphosis” that dominated the world in the first half of the 20th century. Enchanting paintings by Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo or Dorothea Tanning behind the glass, or the photographs by Claude Cahun and Florence Henri on the walls, right next to a video of Josephine Baker dancing. Surrealist works followed by those of Futurists and the Bauhaus, to complete the experience.

Then comes a blue room full of Paula Rego, a theater of human relationships. Domestic scenes that are anything but usual. Charged with tension and complexities that in my view only she can paint. Experiences of women in a world shaped by conflict. Rego died earlier this year, having enjoyed her overdue fame for a few years only. Somehow that makes her artwork all the more powerful, distressing yet defiant, immortal.

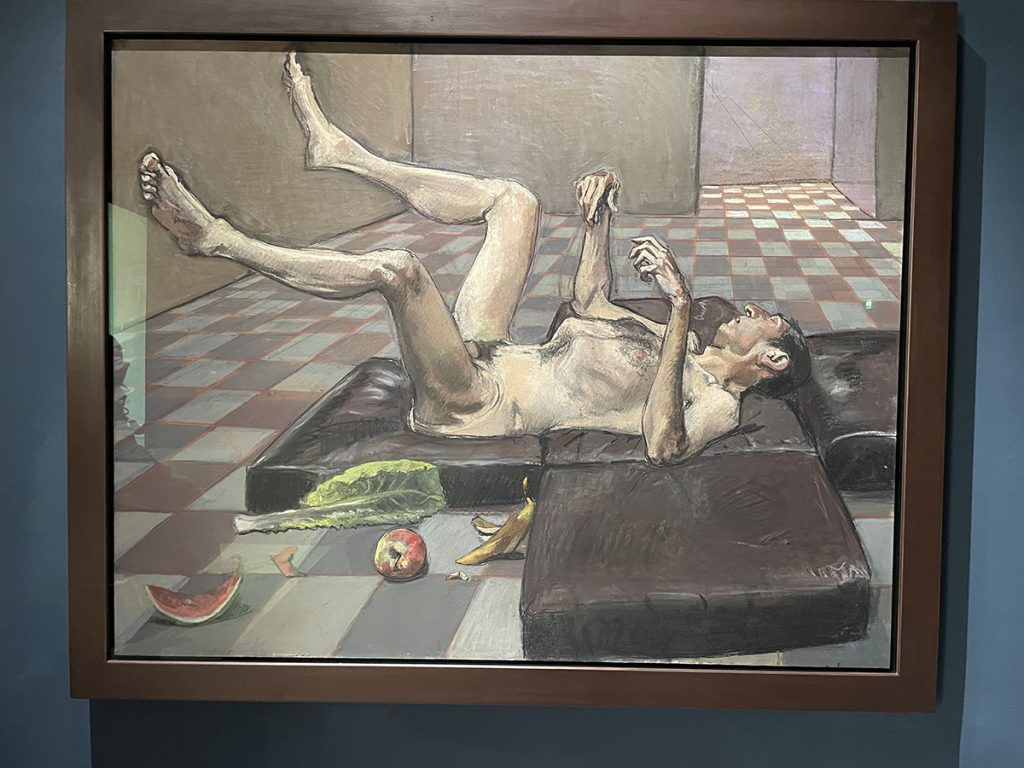

Four regular white walls, with works on paper pinned on them, scarce labeling, an almost amateur-looking art fair booth in the middle of the Venice Biennale. All that is forgotten once you focus on the work on view. Miriam Cahn explores “what she believes to be the innate treachery, brutality, and beauty in the human condition.” It’s like walking into a dreamscape of the human condition, with bodies floating in blurred spaces, gender moving around fluidly, anguish almost palpably taking over the entire space. Cahn’s work is as disquieting as it is mesmerizing, and absolutely breath-taking.

In the Arsenale, the viewing experience is a linear one, thus more enjoyable for me.

Here, one of the more memorable installations include a room filled with Earth, courtesy of Delcy Morelos. A sort of a labyrinth of soil rises above the ground, simultaneously threatening and calming. The artist uses earth as a gesture that refers to her upbringing in the Indigenous territory of the Emberà-Catío people in Tierralta, Colombia. The work is a reminder that we come from and return to earth, and it is earth that has control, not us.

Inside a house-like wooden structure are the works by Chilean artist Sandra Vásquez de la Horra. The female form intricately drawn on paper and then immersed in molten beeswax, evoking the vulnerability of its subjects. Fantasy, fairy tales, dreams and horror all emerge from these works, depicting mortality, rebirth, sexuality, myths, rituals and traditions, religion.

“Seduction of the cyborg”, another capsule, delves into the ways the human and the mechanical merge, particularly relying on the writings of Donna Haraway. In 1985, she repurposed the term “cyborg” to describe the ways the line between human, animal and machine have been blurred, and how the female body is where they are most vulnerable. Here we have Rebecca Horn‘s giant machine sculpture that recreates intimacy, but perhaps the most notable parts include photography by Alexandra Exter, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Marianne Brandt, or Marie Vasilieff. Closing the section are the wonderful works by Kiki Kogelnik, kinds of X-rays of the female body.

Louise Bonnet‘s “Pisser Triptych” is a thrilling example of contemporary oil painting. An ode to Medieval and Renaissance painting, but also Giorgio de Chirico in my head, it shows an excess of bodily fluids leaving the blobby human bodies, becoming waste and fertilizer simultaneously.

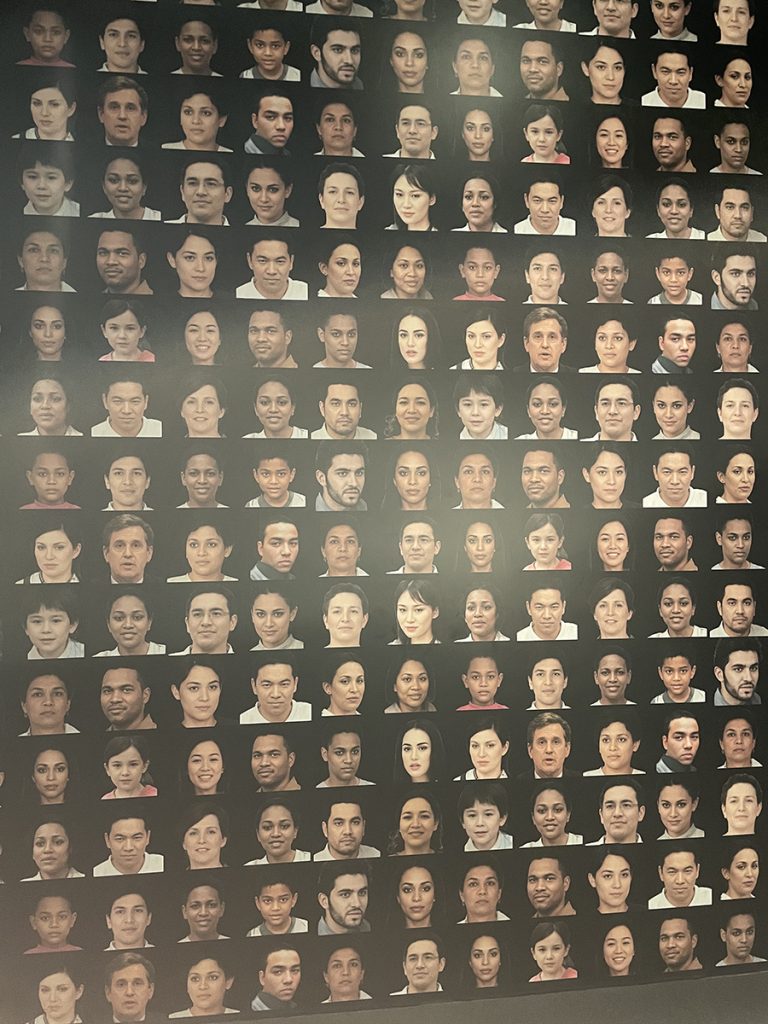

In a dark, black room, an array of human faces is presented. The twist here? None of these people actually exist, but are rather created by AI and artist Lynn Hershman Leeson.

Finally, an ephemeral jungle of sorts by Precious Okoyomon. Effigies are set against a field of wild growth, featuring sugar cane and kudzu – an invasive species of vine widely used in the 1930s and 40s as a means to fortify widespread erosion of local soil degraded by the over cultivation of cotton during slavery. For the artist, the plant becomes a metaphor for the entanglement of slavery, radicalization and diaspora with nature, and how something “invasive” can also be revitalizing.

Venice Biennale 2022 – National Pavilions

The national pavilions, as one would expect, were perhaps a little more political. Naturally, body politics often derive straight from politics, although with some pavilions I failed to recognize that thread if there was one. Others were quite blatant and obvious about it, although many times not in a discouraging way.

My favorites include:

- Switzerland: a sensory experience in all the ways, with wooden sculptures barely visible under pulsating red lights .

- Denmark: inside what appears to be a traditional farmhouse there are two centaurs: half human, half horse, they stare us in the eye, one on the ground dead, and the other hanging from a ceiling. Posing existential questions, the Danish pavilion makes us wonder whether we want this new world or not, whether we should accept changes of our own selves, whether anything makes sense at all.

- The Nordic Pavilion, turned into the Sámi pavilion for the first time, tackling issues indigenous land and people are still facing in present-day Scandinavia.

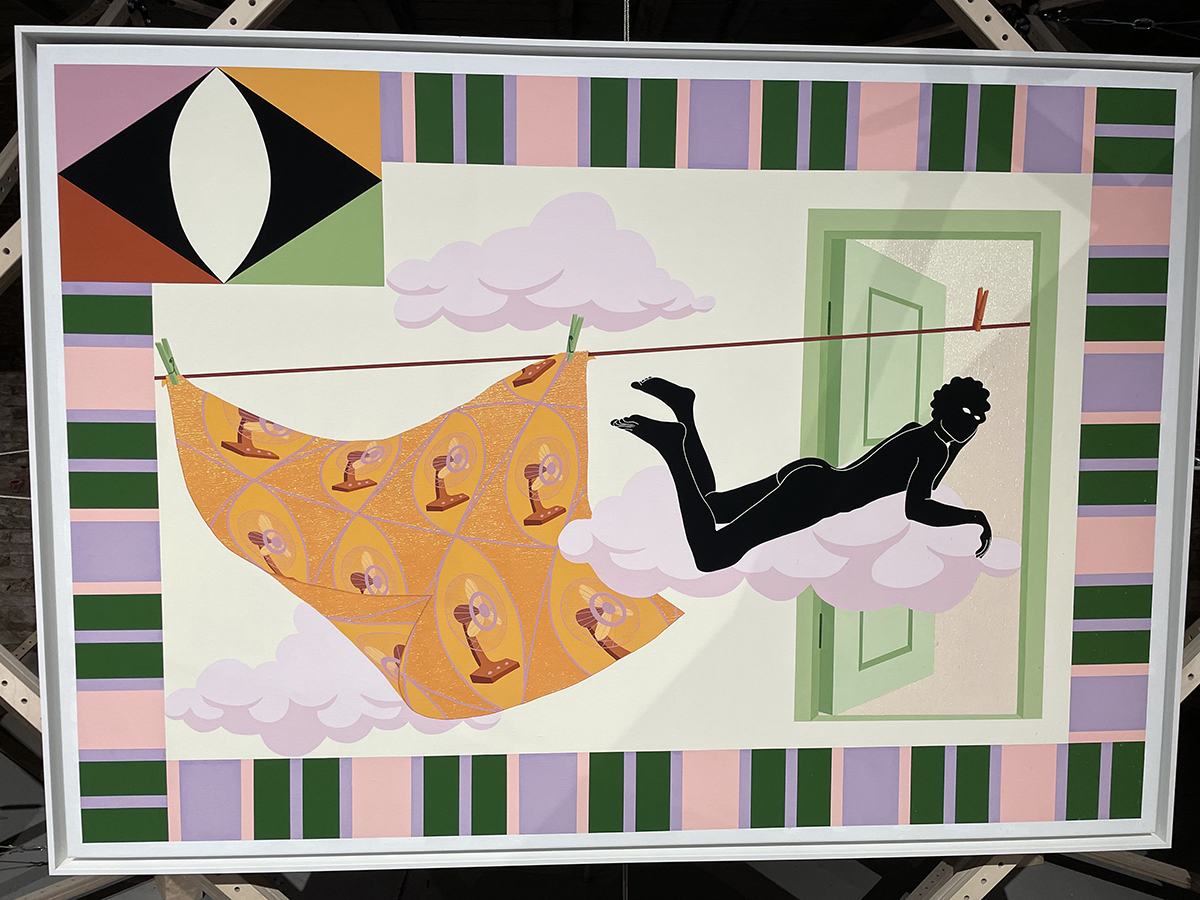

- The US pavilion with Simone Leigh, winner of the Golden Lion award. A pavilion in which the artist parses the construction of Black femme subjectivity. Large-scale sculptures evoking the female body nod to the African and African Diaspora’s artistic traditions and talk of Sovereignty, self-governance, independence, for the individual and the collective.

- Brazil: a pavilion turned into a pulsating human body. An ear installed at the entrance and exit, so visitors could go “in one ear and out the other”, while inside there are eyes, tongues, fingers, a nose, a heart coming out of a mouth.

- Ghana: a pavilion featuring three artists, but it was Na Chainkua Reindorf‘s paintings that left the biggest impression on me. She depicts a fictional secret society made of seven women in such a concise, poignant way.

All images courtesy of the author, exclusively for Live in Italy Mag.