Italian women. What’s the first thing that comes to mind? Stylish. Hard working. Sophisticated. Loud. Beautiful. Revolutionary. Passionate. On this International Women’s Day, March 8 2024, we look at some of the most remarkable “donne italiane” throughout the history of Italy.

From politicians and scientists to artists and fashion designers, these Italian women paved the way for their peers and generations to come. They had different stories at different moments in time, coming from different backgrounds. But what they have in common is that they all had to overcome so much to get to their rightful place in the history of Italy. They challenged conventions and forever changed Il Belpaese and the world at large. We can still see and feel the impact that these incredible women left behind, as we continue to celebrate them and their achievements every day.

These are the stories of perseverance, feminism, and bravery.

I’m well aware that there are many, many more Italian women we did not include in our round-up this International Women’s Day or Festa della Donna. But fret not, as there will be more of these articles! That said, please let us know in the comments which Italian women you admire.

In the meantime, here are 8 Italian women you absolutely need to know, if you don’t already!

Artemisia Gentileschi

We start off with a bang. Artemisia Gentileschi, the great Italian painter, the queen of dramatic Baroque scenes, sometimes even more so than Rembrandt van Rijn! Daughter of a painter, Artemisia was the most talented of his children. She was the first woman to gain membership to the Academy of the Arts of Drawing in Florence in 1616. Her life and work were heavily shadowed by rape and the subsequent trial of one Agostino Tassi.

Thankfully, in recent decades, it is Artemisia’s remarkable paintings that take center stage. One of these is “Judith Slaying Holofernes” (1614–1620), which you should definitely see in person the next time you’re in Florence – at the Uffizi gallery!

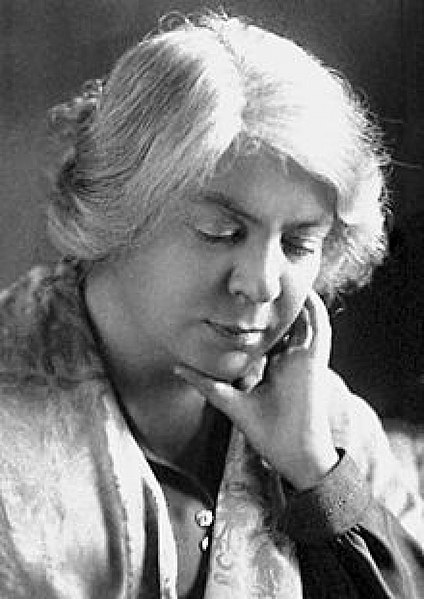

Maria Montessori

You’ve probably heard of Montessori schools, or the Montessori leaning method. But did you know a woman was behind these? We are of course talking about Maria Montessori, a big voice in education and feminism, in Italy and beyond. When she graduated from medical school in 1896, Maria was among the country’s first female physicians. She took an interest in education and educational theory, another male-dominated field. Her story started with La Casa dei Bambini (children’s house) in Rome. There, Maria observed underserved and children with developmental disabilities.

By changing their approach to learning, Maria Montessori gave birth to a worldwide movement, based on self-directed activity, hands-on learning and collaborative play. Today, Maria Montessori’s educational method is used in many public and private schools globally.

Grazia Deledda

As it often happens in articles about women in general, there will be many times you will read phrases like “the first woman” or “the only woman” – or both. This is the case for Grazia Deledda, who was the first Italian woman to win the Nobel Prize.

Born and raised on the island of Sardinia, Grazia had an interest in writing from an early age. Her books often spoke of traditional patriarchal traditions with great emotional force. The motivation behind her 1926 Nobel prize read: “for her idealistically inspired writings which with plastic clarity picture the life on her native island and with depth and sympathy deal with human problems in general.”

Anna Magnani

Perhaps to younger generations there are more famous Italian actors out there – but Anna Magnani was a one-of-a-kind talent. The movie world at the time, which was mid-last century, described Anna using adjectives such as “volcanic” and “explosive”. She was a true icon of the Italian neorealism movement in cinema, starring in movies made by the biggest directors of the time, Italian and American alike.

Anna Magnani was no stranger to portraying emotion, ranging from exuberant comedy to deep grief. She was the first Italian (and first non-English speaking woman) to win an Oscar, for her role in “The Rose Tattoo” (1955), which playwright Tennessee Williams wrote specifically with her in mind.

Nilde Iotti

As Italy switched from being a monarchy to a republic in 1946, Nilde Iotti became one of the pivotal figures on the Italian political scene. Nilde was elected member of the Constituent Assembly, within the Italian Communist Party (PCI), and was also one of the 75 members of the Committee entrusted with the drafting of the Italian Republican Constitution.

After the 1979 Italian general election, Nilde became President of the Chamber of Deputies, ie. the speaker of the lower house of the Italian Parliament. Her first speech was on women’s role in society as well as the fight against terrorism. In 1992, she almost ended up in the hat to become President of the Italian Republic.

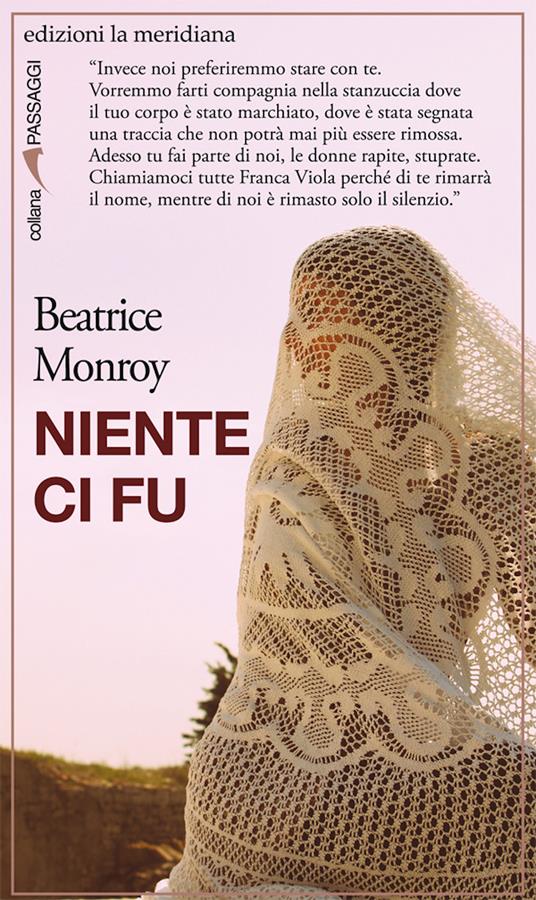

Franca Viola

At age 15, in 1963, the Sicilian girl Franca Viola was engaged to Filippo Melodia, nephew of a mafia boss. When Filippo was arrested for theft, Franca’s father called off the engagement and would not back down under intimidation and violent threats. As revenge, Filippo and 12 others kidnapped, raped and and held Franca for eight days in a farmhouse. The proposed solution was a “rehabilitating marriage” (Italian: matrimonio riparatore) to Filippo. According to the customs of the time, a girl who had been raped would necessarily have to marry her rapist to save her and her family honor. Otherwise, she would have remained a spinster and branded as a “shameless woman”. The rapist’s crime would then not be recognized as such, even when committed against minors.

The Franca Viola trial was groundbreaking, thanks to her courage and saying “no” to a widely accepted and never questioned custom in southern Italy. Despite numerous attempt to discredit Franca, her intentions and her family, Filippo Melodia was sentenced to prison. The case stirred up debate in an evolving Italian republic on the topic of violence against women. Yet, it was only in 1981 that the aforementioned penal code was abolished, and only in 1996 that rape became a “crime against the person”, and not “against morality.”

In March 2014, Franca Viola received an Order of Merit from the Italian President for her bravery.

Rita Levi-Montalcini

Rita Levi-Montalcini was born in Turin to a father who did not approve of women being anything other than wife and mother. After some persuasion, he backed down, and Rita crammed years’ worth of Latin, Greek and math into a few months, so she could enroll in medical school. After graduation, in a life-changing move for us all, she switched to neurology and psychology. As a Jew living in fascist Italy, Rita had a hard time working and conducting research. She built her own laboratory in her bedroom and started studying the motor neurons of chick embryos.

Following her move to the US, at the invitation of a Washington University professor, Rita discovered a substance in the tumor that they named nerve growth factor (NGF). To give you an idea: NGF has given scientists a new way to study neural growth and potentially battle disorders of neural degeneration, such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. NGF is a potential therapeutic target in cancer. It could help treat multiple sclerosis and be a factor in various psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and autism. For this discovery, she got the 1986 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine jointly with colleague Stanley Cohen.

Until her death at 103, Rita also served in the Italian Senate as a Senator for Life. She founded and was the first director of the Institute of Cell Biology in Rome. She also established the Rita Levi-Montalcini Foundation, to provide African women “with the tools for a full development of their capabilities.”

Margherita Hack

“Signora delle stelle”, lady of the stars. I’ll begin Margherita Hack’s story with a premonition, for those who love them. She was born in via Centostelle (“one hundred stars” in Italian) at the corner with Campo di Marte (Fields of Mars) in Florence. A success long-and high-jumper in her youth, she pursued her love of the stars only to become one of world’s leading astrophysicists. She researched Epsilon Aurigae, the multiple star system, the star Zeta Tauri, as well as distant galaxies and fossil radiations. In 1964, she became the first woman in Italy to direct an astronomical observatory in Trieste.

But apart from being a brilliant astrophysicist who worked hard to popularize her field through theatre and books, Margherita was a social and political activist as well. She was an atheist and a vegetarian, was involved in several elections on the local and regional level, and advocated for gay marriage in Italy.